موج لی

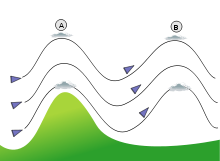

در هواشناسی، امواج لی (به انگلیسی: lee waves)، امواج ساکن جو هستند. رایجترین شکل آن امواج کوهستانی (به انگلیسی: mountain waves) است که امواج گرانشی داخلی جو هستند. اینها در سال ۱۹۳۳ توسط دو خلبان گلایدر آلمانی به نامهای هانس دویچمن و ولف هیرت در بالای کرکونوشه کشف شدند.[۱][۲][۳] آنها تغییرات تناوبی فشار اتمسفر، دما و ارتفاع قائم در جریان هوا هستند که در اثر جابجایی عمودی ایجاد میشوند، برای مثال بالابری کوهساری زمانی که باد بر فراز یک کوه یا رشته کوه میوزد. آنها همچنین میتوانند ناشی از وزش باد سطحی بر فراز دیواره یا فلات باشد،[۴] یا حتی در اثر انحراف بادهای بالایی بر روی یک جریان گرمایی یا راهگوناَبر.

حرکت عمودی باعث تغییرات دوره ای در سرعت و جهت هوا در این جریان هوا میشود. آنها همیشه به صورت گروهی در کنار لی ناهمواری که آنها را تحریک میکند، رخ میدهند. گاهی، امواج کوهستانی میتواند به افزایش میزان بارندگی در سمت بادسوی (به انگلیسی: downwind) رشته کوه کمک کند.[۵] معمولاً یک تاوه آشفته با محور دوران موازی با رشته کوه، در اطراف اولین ناوه ایجاد میشود. به این گردنده میگویند. قویترین امواج لی زمانی ایجاد میشوند که آهنگ کاهش یک لایه پایدار در بالای انسداد، با یک لایه ناپایدار در بالا و پایین نشان دهد.[۶]

بادهای شدید (با وزش باد بیش از ۱۶۱ کیلومتر در ساعت) میتواند در دامنه رشته کوههای بزرگ توسط امواج کوهستانی ایجاد شود.[۷][۸][۹][۱۰] این بادهای قوی میتوانند به رشد و گسترش حریق ناخواسته کمک کنند (از جمله آتشسوزیهای ناخواسته کوهستانهای بزرگ اسموکی ۲۰۱۶ که جرقههای آتشسوزیناخواسته در کوههای اسموکی به مناطق گاتلینبورگ و پیجون فورج دمیده شد).[۱۱]

جستارهای وابسته[ویرایش]

منابع[ویرایش]

- ↑ On March 10, 1933, German glider pilot Hans Deutschmann (1911–1942) was flying over the Riesen mountains in Silesia when an updraft lifted his plane by a kilometer. The event was observed, and correctly interpreted, by German engineer and glider pilot Wolf Hirth (1900–1959), who wrote about it in: Wolf Hirth, Die hohe Schule des Segelfluges [The advanced school of glider flight] (Berlin, Germany: Klasing & Co. , 1933). The phenomenon was subsequently studied by German glider pilot and atmospheric physicist Joachim P. Küttner (1909 -2011) in: Küttner, J. (1938) "Moazagotl und Föhnwelle" (Lenticular clouds and foehn waves), Beiträge zur Physik der Atmosphäre, 25, 79–114, and Kuettner, J. (1959) "The rotor flow in the lee of mountains." GRD [Geophysics Research Directorate] Research Notes No. 6, AFCRC[Air Force Cambridge Research Center]-TN-58-626, ASTIA [Armed Services Technical Information Agency] Document No. AD-208862.

- ↑ Tokgozlu, A; Rasulov, M.; Aslan, Z. (January 2005). "Modeling and Classification of Mountain Waves". Technical Soaring. Vol. 29, no. 1. p. 22. ISSN 0744-8996.

- ↑ "Article about wave lift". Retrieved 2006-09-28.

- ↑ Pagen, Dennis (1992). Understanding the Sky. City: Sport Aviation Pubns. pp. 169–175. ISBN 978-0-936310-10-7.

This is the ideal case, for an unstable layer below and above the stable layer create what can be described as a springboard for the stable layer to bounce on once the mountain begins the oscillation.

- ↑ David M. Gaffin; Stephen S. Parker; Paul D. Kirkwood (2003). "An Unexpectedly Heavy and Complex Snowfall Event across the Southern Appalachian Region". Weather and Forecasting. 18 (2): 224–235. Bibcode:2003WtFor..18..224G. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2003)018<0224:AUHACS>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Pagen, Dennis (1992). Understanding the Sky. City: Sport Aviation Pubns. pp. 169–175. ISBN 978-0-936310-10-7.

This is the ideal case, for an unstable layer below and above the stable layer create what can be described as a springboard for the stable layer to bounce on once the mountain begins the oscillation.

- ↑ David M. Gaffin (2009). "On High Winds and Foehn Warming Associated with Mountain-Wave Events in the Western Foothills of the Southern Appalachian Mountains". Weather and Forecasting. 24 (1): 53–75. Bibcode:2009WtFor..24...53G. doi:10.1175/2008WAF2007096.1.

- ↑ M. N. Raphael (2003). "The Santa Ana winds of California". Earth Interactions. 7 (8): 1. Bibcode:2003EaInt...7h...1R. doi:10.1175/1087-3562(2003)007<0001:TSAWOC>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Warren Blier (1998). "The Sundowner Winds of Santa Barbara, California". Weather and Forecasting. 13 (3): 702–716. Bibcode:1998WtFor..24...53G. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1998)013<0702:TSWOSB>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ D. K. Lilly (1978). "A Severe Downslope Windstorm and Aircraft Turbulence Event Induced by a Mountain Wave". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 35 (1): 59–77. Bibcode:1978JAtS...35...59L. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1978)035<0059:ASDWAA>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Ryan Shadbolt; Joseph Charney; Hannah Fromm (2019). "A mesoscale simulation of a mountain wave wind event associated with the Chimney Tops 2 fire (2016)" (Special Symposium on Mesoscale Meteorological Extremes: Understanding, Prediction, and Projection). American Meteorological Society: 5 pp.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

بیشتر خواندن[ویرایش]

- Grimshaw, R. , (2002). Environmental Stratified Flows. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Jacobson, M. , (1999). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Modeling. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Nappo, C. , (2002). An Introduction to Atmospheric Gravity Waves. Boston: Academic Press.

- Pielke, R. , (2002). Mesoscale Meteorological Modeling. Boston: Academic Press.

- Turner, B. , (1979). Buoyancy Effects in Fluids. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Whiteman, C. , (2000). Mountain Meteorology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

پیوند به بیرون[ویرایش]

- وب سایت رسمی پروژه موج کوهستانی

- مجموعه زمانی از دادههای هواشناسی، عکسهای ماهواره ای و تصاویر ابری از امواج کوهستانی در باریلوچه، آرژانتین (به زبان اسپانیایی)

- در مورد بادهای شدید و گرم شدن فوئن مرتبط با رویدادهای موج کوهستانی در دامنههای غربی کوههای آپالاشی جنوبی

- بررسی وسعت منطقه ای بادهای شدید ناشی از امواج کوهستانی در امتداد دامنههای غربی کوهستانهای آپالاشی جنوبی