پادشاهی فنج

پادشاهی فُنج پادشاهی سنار سلطنت زرقاء/پادشاهی آبی Sennar | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ۱۵۰۴ (میلادی)–۱۸۲۱ (میلادی) | |||||||||

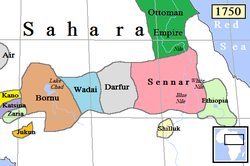

حدود پادشاهی سنار با رنگ صورتی در نقشه نشان داده شدهاست (در پیرامون ۱۷۵۰ میلادی) | |||||||||

| وضعیت | کنفدراسیونی از چند پادشاهی قبایلی تابع پادشاه سنار | ||||||||

| پایتخت | سنار (سودان) ۱۳°۳۳′ شمالی ۳۳°۳۶′ شرقی / ۱۳٫۵۵۰°شمالی ۳۳٫۶۰۰°شرقی | ||||||||

| زبان(های) رایج | عربی[۱] | ||||||||

| دین(ها) | دین سنتی آفریقایی، اسلام[۲] | ||||||||

| حکومت | پادشاهی | ||||||||

| مک (ملک/ سلطان) | |||||||||

• ۱۵۰۴–۱۵۳۳/۴ | عماره دنقس (نخستین) | ||||||||

• ۱۸۰۵–۱۸۲۱ | بادی هفتم (واپسین) | ||||||||

| قوه مقننه | Great Council[۳] | ||||||||

| دوره تاریخی | Early modern period | ||||||||

• بنیانگذاری | ۱۵۰۴ (میلادی) | ||||||||

• فتح به دست نیروهای محمدعلی پاشا | 14 June ۱۸۲۱ (میلادی) | ||||||||

| ۱۳ فوریه ۱۸۴۱ | |||||||||

| جمعیت | |||||||||

• ۱۸۲۰ (میلادی) | 5156000[b] | ||||||||

| واحد پول | هیج (دادوستد پایاپای)[c] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

^ a. Muhammad Ali was granted the non-hereditary governorship of Sudan by an 1841 Ottoman firman.[۴]

^ b. Estimate for entire area covered by modern Sudan.[۵] ^ c. The Funj Sultanate did not mint coins and the markets did not use coinage as a form of exchange.[۶] French surgeon J. C. Poncet, who visited Sennar in 1699, mentions the use of foreign coins such as Spanish reals.[۷] | |||||||||

پادشاهی فُنج یا پادشاهی سنار (به عربی: السلطنة الزرقاء) نام حکومتی سلطنتی بود در شمال سودان کنونی و با مرکزیت سنار (سودان) که توسط قوم فنج پایهریزی شد و از ۱۵۰۴ تا ۱۸۲۱ میلادی از دولتهای مهم شمال شرق آفریقا بود.

نخستین پادشاه این دوده -عماره سنقس- در اوایل سدهٔ شانزدهم میلادی با قومش شهر سنار را گشود و آن را پایتخت خود قرار داد. از ۱۵۲۳ میلادی خاندان سلطنتی فنج رسماً به اسلام گرویدند. اوج اقتدار این دولت در اواخر سدهٔ شانزدهم میلادی بود. در ۱۸۲۱ میلادی نیروهای محمدعلی پاشا وارد سنار شدند و بی مقاومت آنجا را مسخر و به عمر این پادشاهی پایان دادند.

پانویس[ویرایش]

- ↑ McHugh, Neil (1994). Holymen of the Blue Nile: The Making of an Arab-Islamic Community in the Nilotic Sudan, 1500–1850. Series in Islam and Society in Africa. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8101-1069-4.

The spread of Arabic flowed not only from the dispersion of Arabs but from the unification of the Nile by a government, the Funj sultanate, that utilized Arabic as an official means of communication, and from the use of Arabic as a trade language.

- ↑ Trimingham, J. Spencer (1996). "Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa, till the 19th century". The Last Great Muslim Empires. History of the Muslim World, 3. Abbreviated and adapted by F. R. C. Bagley (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-55876-112-4.

The date when the Funj rulers adopted Islam is not known, but must have been fairly soon after the foundation of Sennār, because they then entered into relations with Muslim groups over a wide area.

- ↑ Welch, Galbraith (1949). North African Prelude: The First Seven Thousand Years (snippet view). New York: W. Morrow. p. 463. OCLC 413248. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

The government was semirepublican; when a king died the great council picked a successor from among the royal children. Then—presumably to keep the peace—they killed all the rest.

- ↑ فرمان سلطانی إلی محمد علی بتقلیده حکم السودان بغیر حقالتوارث [Sultanic Firman to Muhammad Ali Appointing Him Ruler of the Sudan Without Hereditary Rights] (به عربی). Bibliotheca Alexandrina: Memory of Modern Egypt Digital Archive. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ Avakov, Alexander V. (2010). Two Thousand Years of Economic Statistics: World Population, GDP, and PPP. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-87586-750-2.

- ↑ Anderson, Julie R. (2008). "A Mamluk Coin from Kulubnarti, Sudan" (PDF). British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan (10): p. 68. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

Much further to the south, the Funj Sultanate based in Sennar (1504/5–1820), did not mint coins and the markets did not normally use coinage as a form of exchange. Foreign coins themselves were commodities and frequently kept for jewellery. Units of items such as gold, grain, iron, cloth and salt had specific values and were used for trade, particularly on a national level.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ↑ Pinkerton, John (1814). "Poncet's Journey to Abyssinia". A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Voyages and Travels in All Parts of the World. Vol. Volume 15. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. p. 71. OCLC 1397394.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)

منابع[ویرایش]

Wikipedia contributors, "Sennar (sultanate)," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sennar_(sultanate)&oldid=687253786 (accessed November 7, 2015).

- انحلالهای ۱۸۲۱ (میلادی) در آفریقا

- ایالات آفریقا پیش از استعمار

- ایالتها و قلمروهای بنیانگذاریشده در ۱۵۰۴ (میلادی)

- ایالتها و قلمروهای منحلشده در ۱۸۲۱ (میلادی)

- بنیانگذاریهای ۱۵۰۴ (میلادی) در آفریقا

- پادشاهیهای گذشته آفریقا

- تاریخ سودان

- دودمانهای مسلمان

- سلطنتهای سابق

- کشورهای پیشین در آفریقا

- کنفدراسیونهای سابق

- کشورهای پیشین